กฎหมายและนโยบายด้านป่าไม้

- รัฐธรรมนูญแห่งราชอาณาจักรไทย พุทธศักราช 2560

- พระราชบัญญัติป่าไม้ พ.ศ. 2484

- พระราชบัญญัติอุทยานแห่งชาติ พ.ศ. 2504 (ฉบับแก้ไข 2562)

- พระราชบัญญัติป่าสงวนแห่งชาติ พ.ศ. 2507

- นโยบายการป่าไม้แห่งชาติ พ.ศ. 2528 (ปัจจุบันอยู่ระหว่างการแก้ไข 2563)

- มติครม. เรื่องการปิดป่าสัมปทาน (17 มกราคม พ.ศ. 2532)1

- พระราชบัญญัติสงวนและคุ้มครองสัตว์ป่า พ.ศ. 2535 (ฉบับแก้ไข 2562)

- พระราชบัญญัติสวนป่า พ.ศ. 2535 และฉบับแก้ไข

- พระราชบัญญัติเลื่อยโซ่ยนต์ พ.ศ. 2545

- ระเบียบสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรีว่าด้วยการจัดให้มีโฉนดชุมชน พ.ศ. 2553

- แผนพัฒนาเศรษฐกิจและสังคมแห่งชาติ พ.ศ. 2560-2564

- พระราชบัญญัติป่าชุมชน พ.ศ. 2562

ประเทศไทยบังคับใช้นโยบายและกฎหมายด้านการจัดการป่าไม้อย่างเป็นระบบและยั่งยืนมานานกว่าสามทศวรรษ ถึงแม้จะพบความท้าทายอย่างมากทั้งในเชิงปฏิบัติ การมีส่วนร่วมและสิทธิของชุมชน2 หลักธรรมาภิบาลจึงถือได้ว่าเป็นปัจจัยบวกที่ส่งเสริมต่อความสมบูรณ์ของป่าไม้ไทย3

นิยามของป่าไม้

โดยทั่วไป “ป่า” หมายถึง ขอบเขตพื้นที่ป่าที่มิได้มีกรรมสิทธิ์ของบุคคลตามกฎหมายที่ดินและไม่เกี่ยวข้องกับป่าปกคลุม ส่วนคำว่า “ป่าสงวน” มีความหมายเฉพาะเจาะจงที่เน้นการดูแลจากภาครัฐ แต่ก็ไม่จำเป็นต้องเป็นป่าปกคลุม ซึ่งภายใต้พระราชบัญญัติป่าไม้ พ.ศ. 2484 และพระราชบัญญัติป่าสงวนแห่งชาติ พ.ศ. 2507 “ป่า” หมายถึงที่ดินสาธารณะทั้งหมดไม่ว่าจะเป็นป่าหรือไม่ก็ตาม4 โดย “ป่าสงวน” “อุทยานแห่งชาติ” และ “เขตรักษาพันธุ์สัตว์ป่า” เป็นหมวดหมู่หลักของที่ดินสาธารณะที่ได้กำหนดไว้อย่างเป็นทางการ (แต่ก็พบบางกรณีที่มีความทับซ้อนกัน)5 แต่ละหมวดหมู่อาจจะรวมถึงป่าไม้ธรรมชาติ และจะมีระดับการดูแลที่แตกต่างกันไป รวมถึงพืชและสัตว์บางสายพันธุ์ยังได้รับการคุ้มครองเป็นพิเศษด้วย ในขณะเดียวกัน ภาครัฐมีแผนงานเพิ่มพื้นที่ป่าปกคลุมให้ได้ตามเป้าหมายมากกว่าร้อยละ 40 ของพื้นที่ทั้งประเทศ6

บางคนเรียกที่ดินสาธารณะเป็น “ป่าตามกฎหมาย” ตามพระราชบัญญัติที่ออกประกาศใช้ในปี 2484 และ 25077จากพื้นที่ทั้งหมดของประเทศทั้งสิ้น 41 ล้านเฮกตาร์ (หรือประมาณ 256.25 ล้านไร่) เป็นป่าอนุรักษ์หรือเขตสงวนจำนวน 23 ล้านเฮกตาร์ (หรือ 143.75 ล้านไร่) โดยปกติจะมีข้อกำหนดเรื่องกิจกรรมที่ได้รับอนุญาตในพื้นที่ป่าสงวนที่ระบุไว้ (อ่านเพิ่มเติม “กิจกรรมที่ได้รับอนุญาต” ด้านล่าง)

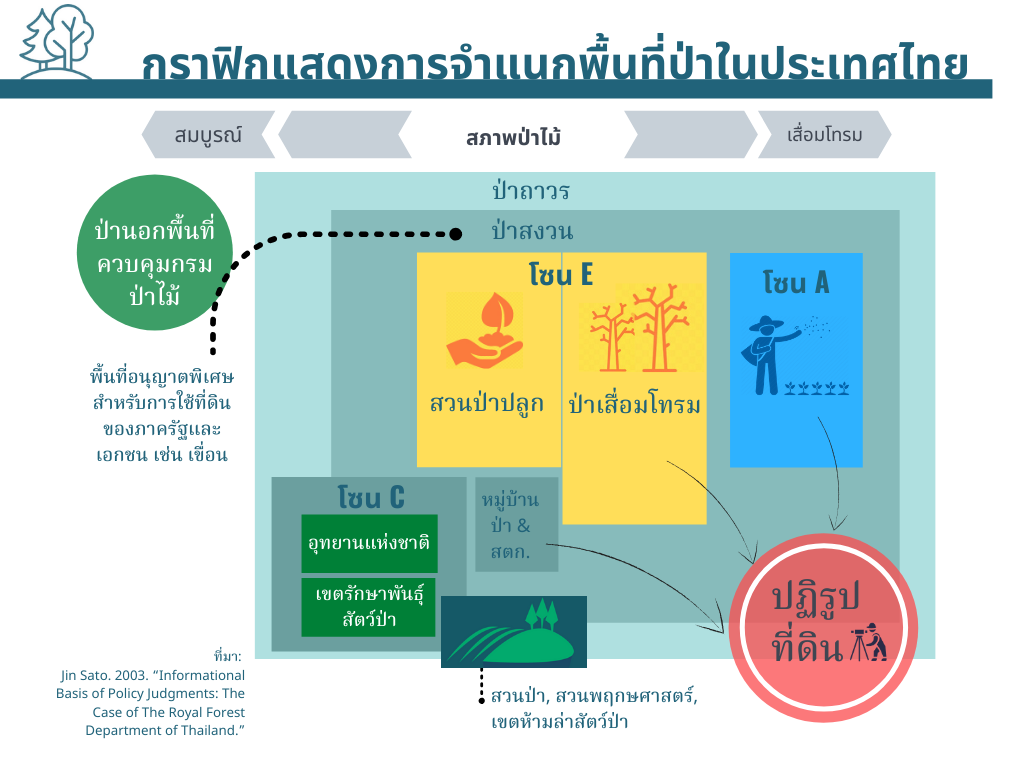

นโยบายการป่าไม้แห่งชาติ พ.ศ. 2528 ได้ระบุหมวดหมู่ย่อยเพิ่มเติมของที่ดินภายใต้ป่าสงวน คือ เขตอนุรักษ์ (Conservation – C) ที่ไม่อนุญาตให้มีการตั้งถิ่นฐานหรือทำกิจกรรมใด ๆ; เขตเศรษฐกิจ (Economic – E) เขตที่อนุญาตให้ทำกิจกรรมเชิงเศรษฐกิจบางอย่าง เช่น การทำป่าปลูก และ/หรือการเก็บเกี่ยวไม้; และเขตเกษตรกรรม (Agriculture – A) ที่เน้นวัตถุประสงค์หลัก คือเพื่อการเกษตร กรมป่าไม้ได้ใช้เกณฑ์นี้ตัดสินการตั้งถิ่นฐานของชุมชนก่อนหรือหลังการจัดตั้งเขตป่าอนุรักษ์ โดยไม่ต้องจำเป็นต้องมีกรรมสิทธิ์ครอบครองอย่างถูกต้องสมบูรณ์8

กราฟิกแสดงการจำแนกพื้นที่ป่าในประเทศไทยด้านล่างนี้นำมาออกแบบให้เข้าใจง่ายยิ่งขึ้น9

ที่ดินสาธารณะสองประเภทที่มีมาตรการปกป้องอย่างเป็นระบบ คือ อุทยานแห่งชาติและเขตรักษาพันธุ์สัตว์ป่า ในปี 2562 พบว่ามีรายงานพื้นที่ทั้งสิ้น 6.7 ล้านเฮกตาร์ (ประมาณ 41.9 ล้านไร่) ในเขตที่กำหนดเป็นอุทยานแห่งชาติจำนวน 100 แห่ง และมีพื้นที่อีกประมาณ 1 ล้านเฮกตาร์ (หรือ 6.25 ล้านไร่) ในเขตที่มีการนำเสนอให้เป็นอุทยานแห่งชาติ นอกจากนี้ มีพื้นที่ประมาณ 3.6 ล้านเฮกตาร์ (หรือ 22.5 ล้านไร่) ในเขตที่กำหนดเป็นเขตรักษาพันธุ์สัตว์ป่า 56 แห่งและ 13,400 เฮกตาร์ (หรือ 83,750 ไร่) ในเขตที่มีการนำเสนอให้เป็นเขตรักษาพันธุ์สัตว์ป่าใหม่ 2 แห่ง10 การแก้ไขเพิ่มเติม พ.ร.บ. อุทยานแห่งชาติและ พ.ร.บ. สงวนและคุ้มครองสัตว์ป่าทั้งสองฉบับเพิ่งได้ผ่านการพิจารณาอนุมัติในช่วงกลางปี 2562 ที่ผ่านมา และจะมีผลบังคับใช้ในเดือนพฤศจิกายนในปีเดียวกัน สิ่งสำคัญ คือ สวนป่าและสวนพฤกษศาสตร์จะได้รับความคุ้มครองเช่นเดียวกับอุทยานแห่งชาติ และได้เพิ่มบทลงโทษอาชญากรรมที่เกี่ยวกับสัตว์ป่าต่าง ๆ11

พระราชบัญญัติสวนป่า พ.ศ. 2535 ว่าด้วยการปลูกป่าเชิงพาณิชย์สามารถดำเนินการได้ในพื้นที่ป่าเสื่อมโทรมภายใต้การกำกับขององค์การอุตสาหกรรมป่าไม้ หรือในที่ดินส่วนบุคคลที่มีใบอนุญาตที่ถูกต้อง12 ป่าสงวนในปัจจุบันจึงนับรวมทั้งป่าธรรมชาติและสวนป่า13

ผู้รับผิดชอบจัดการป่าไม้หลักคือใคร?

ปัจจุบัน มีสองกรมหลักภายใต้กระทรวงทรัพยากรธรรมชาติและสิ่งแวดล้อมแบ่งหน้าที่รับผิดชอบการจัดการป่าไม้ คือ กรมป่าไม้ (Royal Forest Department – RFD) ดูแลป่าสงวนและกำกับสวนป่าเชิงพาณิชย์ของภาคเอกชน และกรมอุทยานแห่งชาติ สัตว์ป่า และพันธุ์พืช (Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation – DNP) ดูแลบริหารอุทยานแห่งชาติและเขตอนุรักษ์พันธุ์สัตว์ป่า ซึ่งรวมถึงป่าในพื้นที่ด้วย ทั้งสองหน่วยงานแบ่งความรับผิดชอบพร้อมทำงานร่วมกับตำรวจแห่งชาติเพื่อบังคับใช้บทบัญญัติแห่งกฎหมายเกี่ยวกับความผิดทางอาญาที่ควบคุมแต่ละอาณาเขต

กรมป่าไม้ ประกอบด้วยเจ้าหน้าที่ระดับจังหวัด อำเภอ และป่าสงวนแต่ละพื้นที่14 เจ้าหน้าที่ระดับอำเภอและจังหวัดจะรายงานต่อผู้ว่าราชการจังหวัดและข้าราชการประจำอำเภอซึ่งขึ้นตรงต่อกระทรวงมหาดไทย15

หน้าที่ความรับผิดชอบของกรมป่าไม้ ได้แก่

- ออกแบบแผนการจัดการป่าสงวนแต่ละแห่ง

- ออกใบอนุญาตเพื่อการเก็บรวบรวมผลิตภัณฑ์ที่ได้จากป่า

- บังคับใช้กฎหมายและข้อบังคับที่เกี่ยวกับป่าสงวน

ป่าชุมชน

ชุมชนที่อาศัยอยู่ในเขตป่าและพื้นที่ใกล้เคียงได้ร่วมรณรงค์อย่างต่อเนื่องเรื่องสิทธิในที่ดินทำกินตามกฎหมาย ภายหลังการประกาศเขตป่าสงวนและเขตอนุรักษ์ที่ทับซ้อนที่ทำกินและอยู่อาศัยของประชาชน แต่กลับไม่ประสบความสำเร็จเท่าที่ควร หลายปีที่มา กรมป่าไม้ได้พิสูจน์สิทธิ์รับรองป่าชุมชนกว่า 7,000 แห่ง โดยให้ชุมชนมีสิทธิ์เก็บของป่าเพื่อการบริโภคในครัวเรือนเท่านั้น (และยังมีป่าชุมชนอีกกว่า 3,000 แห่งที่มีอยู่ แต่ยังไม่ได้รับรองอย่างเป็นทางการ)16 จนกระทั่งเมื่อไม่นานนี้ มีมาตรการแก้ไขให้สิทธิที่ดินทำกินตามข้อตกลงโดยไม่ต้องอ้างอิงกฎหมาย17

เอกสารความพร้อม REDD ของประเทศไทยที่นำเสนอต่อกองทุนหุ้นส่วนคาร์บอนป่าไม้ (Forest Carbon Partnership Facility – FCPF) อ้างอิงถึงมาตรา 19 ของพระราชบัญญัติป่าสงวน โดยให้เป็นอำนาจแก่อธิบดีกรมป่าไม้ในการจัดการป่าไม้18 โดยระเบียบสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรีว่าด้วยการจัดให้มีโฉนดชุมชน พ.ศ. 2553 ระบุให้ชุมชนมีสิทธิในการใช้งานแต่ไม่มีกรรมสิทธิ์ในที่ดินของรัฐ นอกจากนี้ ยังมีมติให้มีการลงทะเบียนด้านสิทธิเป็นระยะ ๆ19

อย่างไรก็ตาม ในเดือนกุมภาพันธ์ 2562 ที่ผ่านมา สภานิติบัญญัติแห่งชาติ (สนช.) มีมติเห็นชอบผ่านร่างพระราชบัญญัติป่าชุมชน ซึ่งมีผลประกาศใช้ในเดือนพฤศจิกายนของปีเดียวกัน พ.ร.บ. นี้ให้การยอมรับการจัดตั้งป่าชุมชนในเขตป่าอนุรักษ์อย่างเป็นทางการ ถึงแม้ว่ารัฐบาลจะยังคงสิทธิในการครอบครองทั้งหมด20 อย่างไรก็ดี พ.ร.บ. นี้ยังไม่ยอมรับสิทธิของป่าชุมชนในเขตอุทยานแห่งชาติ เขตรักษาพันธุ์สัตว์ป่า หรือพื้นที่คุ้มครองอื่น ๆ21

เมื่อไม่นานนี้ รายงานวิเคราะห์เชิงกฎหมายของพระราชบัญญัติป่าชุมชนยืนยันให้เห็นว่าการตราพระราชบัญญัติป่าชุมชนเป็นขั้นตอนสำคัญในการเสริมสร้างการยอมรับบทบาทของชุมชนในการจัดการป่าไม้นอกพื้นที่ป่าคุ้มครองอย่างเป็นทางการ ในบทวิเคราะห์ยังได้ระบุช่องว่างทางกฎหมายที่สำคัญ คือสมาชิกในชุมชนได้รับอนุญาตให้ใช้ผลิตภัณฑ์จากป่าเพื่อการยังชีพเท่านั้น ห้ามใช้เพื่อการค้า22

ป่าชุมชนดีเด่น อ.ท่าแซะ จ.ชุมพร ที่มา: ไทยรัฐออนไลน์, CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0.

กิจกรรมในเขตป่าใดบ้างที่ได้รับอนุญาต และใครมีอำนาจดูแล?

การเข้าครอบครองที่ดินสาธารณะใด ๆ ถือเป็นสิ่งต้องห้าม แต่ในทางปฏิบัติ จะห้ามการถือครองพื้นที่ในป่าที่ยังไม่ได้รับรองเป็นเขตอนุรักษ์ตามกฎหมาย โดยเฉพาะตามเนินเขา ภูเขา และในระยะที่ 40 เมตรจากเชิงเขาหรือภูเขาเท่านั้น23 พ.ร.บ. ป่าสงวนแห่งชาติ พ.ศ. 2507 ระบุว่าการตัดไม้และการเก็บของป่าทุกชนิดจะต้องได้รับอนุญาตตามกฎหมายเท่านั้น24

พระราชบัญญัติป่าไม้ปี พ.ศ. 2484 ได้กำหนดไม้หวงห้ามทั่วประเทศไว้ 2 ประเภทหลัก: ประเภท ก. ไม้หวงห้ามธรรมดา (รวมถึงไม้สัก) ซึ่งการทำไม้จะต้องได้รับอนุญาตจากพนักงานเจ้าหน้าที่ และประเภท ข. ไม้หวงห้ามพิเศษ ซึ่งไม่อนุญาตให้ทำไม้ เว้นแต่รัฐมนตรีจะได้อนุญาตในกรณีพิเศษ25 อย่างไรก็ตาม การทำไม้ในพื้นที่สาธารณะทุกประเภทมีผลยุติลงทันทีตั้งแต่มีประกาศใช้มติครม.ปิดป่าสัมปทาน พุทธศักราช 2532

นอกจากนี้ การครอบครองหรือใช้ที่ดินในป่าสงวนแห่งชาติเพื่อการเกษตรถือเป็นการกระทำที่ขัดต่อพระราชบัญญัติป่าสงวนแห่งชาติ พ.ศ. 2507 โดยมีข้อยกเว้นบางประการ คือ 1) เป็นผู้ที่ประกอบอาชีพหรือใช้ที่ดินในเขตป่าสงวนแห่งชาติก่อนล่วงหน้าวันที่พระราชบัญญัตินี้ใช้บังคับ และได้ยื่นคำขออนุญาตภายใน 90 วันหลังจากการกำหนดเป็นป่าสงวนแห่งชาติ และ 2) ผู้ที่ได้รับสัมปทานหรือได้รับอนุญาตพิเศษเพื่อเข้าทำประโยชน์หรืออยู่อาศัยในเขตป่าสงวนแห่งชาติแล้ว ข้อยกเว้นเหล่านี้ และคำอธิบายเขต A และ E จากแผนภาพข้างต้นถือเป็นข้อมูลที่มีนัยสำคัญเมื่อคำนึงถึงขนาดประชากรที่อาศัยในเขตป่าสงวนแห่งชาติ

ภายใต้พระราชบัญญัติอุทยานแห่งชาติ พ.ศ. 2504 ห้ามมิให้มีการจัดเก็บหรือทำอันตรายต่อทรัพยากรธรรรมชาติ ซึ่งรวมถึงพืชพันธุ์ต่าง ๆ ในเขตอุทยานแห่งชาติ และไม่อนุญาตให้ประกอบอาชีพใด ๆ ในพื้นที่เขตอุทยาน26 นับได้ว่าการบังคับใช้พระราชบัญญัตินี้มีความเข้มงวดมากกว่ามาตรการของเขตป่าสงวน และมีความท้าทายอย่างมาก เนื่องจากคาดการณ์ว่ามีประชากรกว่าหนึ่งล้านคนที่อยู่อาศัยทำกินในเขตอุทยานแห่งชาติทั่วประเทศ27 โดยข้อบังคับภายใต้พระราชบัญญัติป่าสงวนและคุ้มครองสัตว์ป่า พ.ศ. 2535 มีความคล้ายคลึงเช่นกัน28

ตารางที่ 1: หน่วยงานหลักและหน้าที่รับผิดชอบต่อป่าไม้

| หน่วยงาน | หน้าที่รับผิดชอบ | |

|---|---|---|

| กระทรวงทรัพยากรธรรมชาติและสิ่งแวดล้อม (Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment) | กำกับการทำงานของ 3 กรมหลัก คือ ปม. อ.อ.ป. และ อส. | |

| กรมป่าไม้ (Royal Forest Department) | หน่วยงานสังกัด ทส. รับผิดชอบดูแลภาคป่าไม้และจัดการป่าที่รัฐเป็นเจ้าของ และอยู่นอกพื้นที่อนุรักษ์29 | |

| องค์การอุตสาหกรรมป่าไม้ (Forest Industry Organization) | รัฐวิสาหกิจดำเนินธุรกิจทำไม้สังกัด ทส. ที่ดูแลจัดการสวนป่า | |

| กรมอุทยานแห่งชาติ สัตว์ป่า และพันธุ์พืช (Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation) | หน่วยงานสังกัด ทส. จัดการป่าสงวนของประเทศ | |

| กระทรวงเกษตรและสหกรณ์ (Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives) | ดูแลสวนยางพาราเชิงพาณิชย์ | |

| กระทรวงมหาดไทย (Ministry of Interior) | ดูแลหน่วยงานระดับตำบล อำเภอ และจังหวัดที่มีบทบาทสำคัญในการตัดสินใจจัดการทรัพยากรธรรมชาติ และมีหน่วยสืบสวนในสังกัดที่ตรวจสอบรายงานการตัดไม้อย่างผิดกฎหมาย30 | |

| กระทรวงพาณิชย์ (Ministry of Commerce) | กรมศุลกากรตรวจสอบความถูกต้องของการนำเข้า-ส่งออกไม้ |

ปรับปรุงล่าสุด: 31 สิงหาคม 2564

References

- 1. สรุปประเด็น คือ คณะรัฐมนตรีมีมติเห็นชอบให้รัฐมนตรีว่าการกระทรวงเกษตรและสหกรณ์สั่งการให้สัมปทานทำไม้หวงห้ามทุกชนิด (ยกเว้นสัมปทานทำไม้ป่าชายเลน) ตามพระราชบัญญัติป่าไม้ พ.ศ…. 2484 ทุกสัมปทานสิ้นสุดลงทั้งแปลง ตามที่กระทรวงเกษตรและสหกรณ์เสนอและอนุมัติให้ดำเนินการต่อไปได้

- 2. Voices for Mekong Forests. 2561. “การประเมินการกำกับดูแลป่าไม้ในประเทศไทย.” เข้าถึงเดือนตุลาคม 2562.

- 3. องค์การอาหารและการเกษตรแห่งสหประชาชาติ. 2561. “การเปลี่ยนแปลงของป่าไม้ในอนุภูมิภาคลุ่มแม่น้ำโขง (GMS): ภาพรวมของแรงผลักดันเชิงบวกและลบ.” เข้าถึงเดือนตุลาคม 2562.

- 4. ราชอาณาจักรไทย. 2484. พระราชบัญญัติป่าไม้ พ.ศ. 2484.” เข้าถึงเดือนตุลาคม 2562. พระราชบัญญัติป่าไม้ ระบุว่า: “ในพระราชบัญญัตินี้ (1) ‘ป่า’ หมายถึงที่ดินที่ยังมิได้มีบุคคลได้มาตามกฎหมายที่ดิน” ในขณะที่พระราชบัญญัติป่าสงวนแห่งชาติ พ.ศ. 2507 ระบุว่า: “ในพระราชบัญญัตินี้ ‘ป่า’ หมายความว่าที่ดิน รวมตลอดถึง ภูเขาห้วย หนอง คลอง บึง บาง ลำน้ำ ทะเลสาบ เกาะ และที่ชายทะเลที่ยังมิได้มีบุคคลได้มาตามกฎหมาย

- 5. EU FLEGT Facility. 2554. “การศึกษาข้อมูลพื้นฐาน ครั้งที่ 5 ของประเทศไทย: ภาพรวมของการบังคับใช้กฎหมาย การกำกับดูแล และการค้าป่าไม้ (FLEGT).” เข้าถึงเดือนตุลาคม 2562.

- 6. สำนักงานสภาพัฒนาการเศรษฐกิจและสังคมแห่งชาติ. 2560. “แผนพัฒนาเศรษฐกิจและสังคมแห่งชาติ ฉบับที่ 12 (พ.ศ. 2560-2564).” เข้าถึงเดือนตุลาคม 2562.

- 7. Jean Phillipe LeBlond. 2562. “คำอธิบายของการเปลี่ยนผ่านป่าครั้งใหม่: บทบาทของปัจจัย “ผลักดัน” และกลยุทธ์การปรับตัวต่อการขยายพื้นที่ป่าในตอนเหนือของจังหวัดเพชรบูรณ์ ประเทศไทย.” เข้าถึงเดือนตุลาคม 2562.

- 8. จิน ซาโตะ. 2546. “เกณฑ์ข้อมูลเพื่อการตัดสินเชิงนโยบาย: กรณีของกรมป่าไม้แห่งประเทศไทย.” เข้าถึงเดือนตุลาคม 2562.

- 9. อ้างแล้ว. เข้าถึงเดือนตุลาคม.

- 10. Protected Planet. “World Database on Protected Areas: Thailand.” เข้าถึงตุลาคม 2562.

- 11. ธนดี พันธุมโกมล และ แพรว แอนเนซ. ติลลิกี แอนด์ กิบบินส์. 2562. “อัพเดทกฎหมายสิ่งแวดล้อมของประเทศไทย.” เข้าถึงตุลาคม 2562.

- 12. ราชอาณาจักรไทย. 2535. “พระราชบัญญัติสวนป่า พ.ศ. 2535.” เข้าถึงตุลาคม 2562.

- 13. Jean Phillipe LeBlond. 2562. “คำอธิบายของการเปลี่ยนผ่านป่าครั้งใหม่: บทบาทของปัจจัย “ผลักดัน” และกลยุทธ์การปรับตัวต่อการขยายพื้นที่ป่าในตอนเหนือของจังหวัดเพชรบูรณ์ ประเทศไทย.” เข้าถึงเดือนตุลาคม 2562.

- 14. จิน ซาโตะ. 2546. “เกณฑ์ข้อมูลเพื่อการตัดสินเชิงนโยบาย: กรณีของกรมป่าไม้แห่งประเทศไทย.” เข้าถึงเดือนตุลาคม 2562.

- 15. อ้างแล้ว. เข้าถึงเดือนตุลาคม 2562.

- 16. ความริเริ่มด้านสิทธิและทรัพยากร. 2555. “ประเทศไทย: ความคิดเห็นทั่วไป.” เข้าถึงเดือนตุลาคม 2562.

- 17. อ้างแล้ว. เข้าถึงเดือนตุลาคม 2562.

- 18. ราชอาณาจักรไทย. 2556. “ข้อเสนอการเตรียมความพร้อม (R-PP) ของประเทศไทย (ฉบับปรับปรุง).” เข้าถึงเดือนตุลาคม 2562.

- 19. ความริเริ่มด้านสิทธิและทรัพยากร. 2555. “ประเทศไทย: ความคิดเห็นทั่วไป .” เข้าถึงเดือนตุลาคม 2562.

- 20. Rina Chandran. สำนักข่าวรอยเตอร์. 2562 “ร่างกฎหมายป่าชุมชนไทยไม่ได้เป็นประโยชน์กับทุกคน นักรณรงค์กล่าว.” เข้าถึงตุลาคม 2562.

- 21. อ้างแล้ว. เข้าถึงเดือนตุลาคม 2562.

- 22. Nathalie Faure. รีคอฟ. 2564. Legal assessment of Thailand Community Forest Act shows ways to strengthen regulations. เข้าถึงเมื่อ 31 สิงหาคม 2564.

- 23. Jean Phillipe LeBlond. 2562. “คำอธิบายของการเปลี่ยนผ่านป่าครั้งใหม่: บทบาทของปัจจัย “ผลักดัน” และกลยุทธ์การปรับตัวต่อการขยายพื้นที่ป่าในตอนเหนือของจังหวัดเพชรบูรณ์ ประเทศไทย.” เข้าถึงเดือนตุลาคม 2562.

- 24. ราชอาณาจักรไทย. 2507. “พระราชาบัญญัติป่าสงวนแห่งชาติ พ.ศ. 2507.” เข้าถึงเดือนตุลาคม 2562.

- 25. ราชอาณาจักรไทย. 2484. “พระราชบัญญัติป่าไม้ พุทธศักราช 2484.” เข้าถึงเดือนตุลาคม 2562.

- 26. ราชอาณาจักรไทย. 2504. “พระราชบัญญัติอุทยานแห่งชาติ พ.ศ. 2504 (ฉบับแก้ไข 2562).” เข้าถึงเดือนตุลาคม 2562.

- 27. EU FLEGT Facility. 2554. “การศึกษาข้อมูลพื้นฐาน ครั้งที่ 5 ของประเทศไทย: ภาพรวมของการบังคับใช้กฎหมาย การกำกับดูแล และการค้าป่าไม้ (FLEGT).” เข้าถึงเดือนตุลาคม 2562.

- 28. ราชอาณาจักรไทย. 2535. “พระราชบัญญัติสงวนและคุ้มครองสัตว์ป่า พ.ศ. 2535 (ฉบับแก้ไข 2562).” เข้าถึงเดือนตุลาคม 2562.

- 29. EU FLEGT Facility. 2554. “การศึกษาข้อมูลพื้นฐาน ครั้งที่ 5 ของประเทศไทย: ภาพรวมของการบังคับใช้กฎหมาย การกำกับดูแล และการค้าป่าไม้ (FLEGT).” เข้าถึงเดือนตุลาคม 2562.

- 30. EU FLEGT Facility. 2554. “การศึกษาข้อมูลพื้นฐาน ครั้งที่ 5 ของประเทศไทย: ภาพรวมของการบังคับใช้กฎหมาย การกำกับดูแล และการค้าป่าไม้ (FLEGT).” เข้าถึงเดือนตุลาคม 2562.