The coronavirus pandemic has been a challenging time for decision makers globally to respond accurately and in a timely manner to mitigate impacts while keeping the public informed. In fact, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to the intensification of inequality and so far disrupted income growth across the world in the first half of 2020.

Thailand was put under lockdown from mid-March until June 2020. This, and other COVID-19 measures, has significantly affected jobs and workers in Q2, according to the labor force data of Thailand National Statistics Office (NSO).

Check out Dashboard: COVID-19 and Thai Labor Market

Unemployment is a looming concern. According to NSO’s data, the unemployment rate has increased to 2 percent in Q2 of 2020. This is more than three times Thailand’s jobless rate for the last decade, which hovered around 0.6%.1 The Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council (NESDC) estimated that 8.4 million jobs would be at risk from the COVID-19 outbreak in Q2 and Q3 of 2020, in addition to the six million farmers already impacted by drought.2 Thailand’s key sectors have been especially hit. An International Labor Organisation’s (ILO) report predicted that six million or more workers would lose their jobs in Thailand’s tourism industry, which has been strongly impacted by transmission control and social distancing measures.3

COVID-19 has not impacted all labor sectors to the same degree, with the Federation of Informal Workers in Thailand (FIT), reporting that small businesses are earning 20% or less of their pre-COVID-19 income. Others are working reduced hours or working from home, and still others have lost their jobs entirely.4 Those working in informal employment, already vulnerable prior to the pandemic, have been particularly impacted.

Vulnerable informal employment

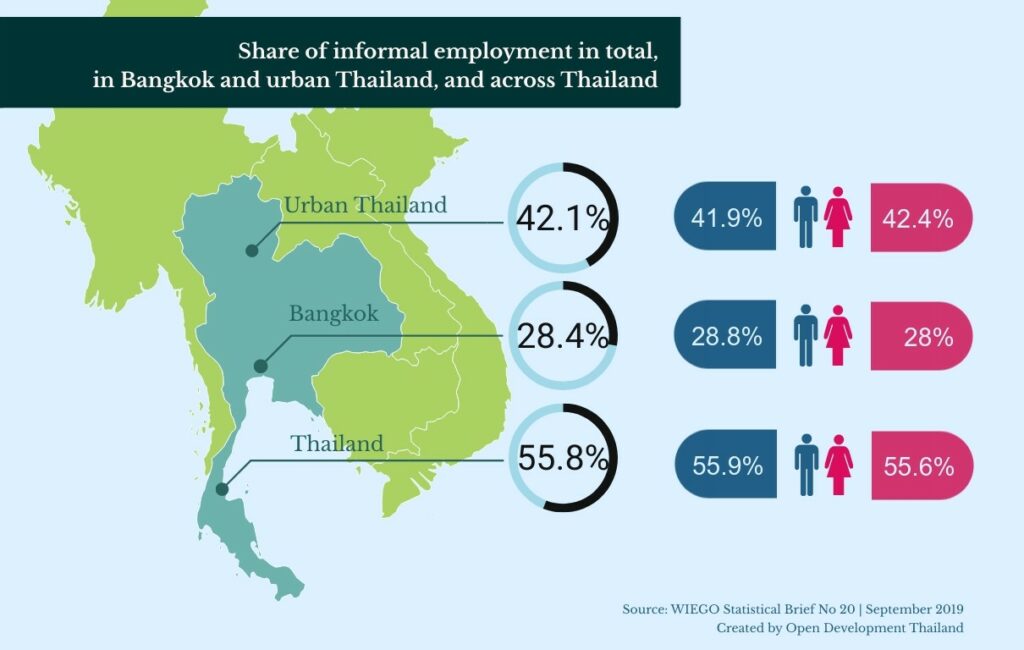

Informal work, which refers to employment that is not covered under a social security scheme, employs more than half of the employed in Thailand, or over 20 million people.5 Informal workers in Thailand are commonly employed in family-run businesses or are self-employed, are paid day wages or have unsecured contracts.6 Some informal employment is referred to as “gigs”, which refers to contractors, freelancers, and short-term contract workers who are hired for short assignments. These occupations range widely, including but not limited to farmers, street vendors, construction workers, motorcycle taxi drivers, and more.7 The increasing number of informal workers is a particularly urban issue, especially with the increase of online applications that support this kind of work. In an urban society that is increasingly digital, informal workers represent around 28 percent of employment in Bangkok, and account for 42 percent in urban Thailand.8

During usual economic downturns, the informal sector compensates for the loss of formal jobs, helping displaced workers to generate their own income and lessening reliance on government benefits. But, COVID-19 measures have hit the informal sector especially hard. The loss of income among informal workers will push many over the poverty threshold (minimum income of about THB 60 or $1.90 per day). As a result, the share of the working poor in Thailand is expected to increase from 4.7 percent to at least 11 percent of total employment this year.9 In particular, lockdowns have hurt market vendors and small-scale traders, while the decline of formal tourism and manufacturing has dented the informal businesses that operate around these sectors, from delivery drivers to street-side vendors.

The impact on household welfare is also likely to be severe. The number of economically insecure, i.e., those living below about THB 173 or $5.50 per day, are projected to double from 4.7 million in Q1/2020 to an estimated 9.7 million in Q2/2020, before recovering slightly to 7.8 million in Q3 2020.10

Thailand’s Gig Economy

While the gig economy is by no means new, it has recently gained new notoriety especially in urban areas due to ‘new normal’ consumers and the emergence of online applications for contracting services. At present, there are a number of applications such as LINE, Grab, Food Panda, Gojek and Get, etc., offering users unified platforms to order food from a variety of restaurants, ranging from large global franchises to street-side stalls. Each delivery is made by a contractless rider who accepts the job or “gig” via the app and is paid per trip. A similar system is in place for motorcycle taxis.

It is difficult to present clear and accurate numbers on labor conditions in the gig economy, in part because food-delivery apps are not regulated by the government. This also means that these gig workers are not protected under social services, although efforts to extend social security protection to all–formal and informal–workers are ongoing. Recent research estimated the earning of platform-based food delivery riders to be in the range of THB 15,000 to 40,000 per month, or US$478-$1274. Riders are motivated to make as many deliveries and work as many hours as possible for higher income. With the piece-rate pay, riders’ income is irregular, with minimum to no job security or worker’s benefits.11

Due to the precarity of gig work, motorcycle taxi drivers are most likely being hit the hardest by pandemic measures, and they could face prolonged effects even after the pandemic. Movement restrictions during the pandemic have boosted on-demand food delivery where ‘new normal’ consumption patterns offer a readily fertile market. Prohibited from dining-in, customers in quarantine can only order food for takeaway or through food delivery platforms. Yet, this potentially exposes drivers to the virus, posing a threat to personal health. Motorcycle taxi drivers have been especially impacted due to the reduced need for transportation, as regular passengers now work from home to maintain social distancing.

Motorbike taxi in Thailand by ibeeckmans | CC Search under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

A Model of Solidarity Economy: Tamsang-Tamsong

To tackle challenges on job security for motorcycle taxi drivers and food vendors, a community-based “Tamsang-Tamsong” (Food Ordered, Passengers Delivered) platform was developed by Chulalongkorn University and Thai Health Promotion Foundation, and promoted in accordance with social distancing measures. The platform intends to strengthen the wellbeing of the community in the Ladprao 101 area in Bangkok by assisting food vendors, motorcycle taxi drivers, and customers in transitioning to a platform economy.

Using a solidarity economy framework, the model can help to increase job security and empower communities, even when social-distancing measures are no longer in effect. Currently, over 60 food vendors and 34 motorcycle taxi drivers have participated in the platform. 12

References

- 1. Asia Times. May 29, 2020. Mass unemployment the new normal in SE Asia. Accessed in August 2020.

- 2. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and The World Bank. 2020. Thailand Economic Monitor: Thailand in the Time of COVID-19. Accessed in August 2020.

- 3. ILO. 202o. ILO Brief: COVID-19 employment and labor market impact in Thailand. Accessed in August 2020.

- 4. Ibid.

- 5. Ibid.

- 6. Ibid.

- 7. The Bangkok Post. 1 May 2020. A Crisis for Workers. Accessed in August 2020.

- 8. Women in Informal Employment Globalizing and Organizing. 2019. WIEGO Statistical Brief No 20: Informal Workers in Urban Thailand: A Statistical Snapshot. Accessed in September 2020.

- 9. Ibid.

- 10. Ibid.

- 11. Just Economy and Labor Institute (JELI). 14 July 2020. Solidarity in precarity: food delivery riders in Thailand’s gig economy. Accessed in August 2020.

- 12. Voice TV. 25 June 2020. ‘Food delivery service’ receives good pay but works exhaustedly, without a secured fund. Accessed in August 2020.